Scaling laws, emergent behaviour and inverse scaling

Recently, I looked into scaling laws for training LLMs. This page contains my notes on this subject.

Table of contents

- Context

- Scaling laws, 2020-2022

- Emergent behaviour in large language models

- Are emergent properties of LLMs a mirage?

- Exceptions to scaling - inverse scaling prize

Context

Why are scaling laws relevant? Training big models takes a long time and is expensive, so it would be helpful if we can get information about the performance of big models, without actually having to train them. This is the practical promise of scaling laws: if we can predict the performance of larger models based on the performance of smaller models, we can save a lot of time and money.Scaling laws, 2020-2022

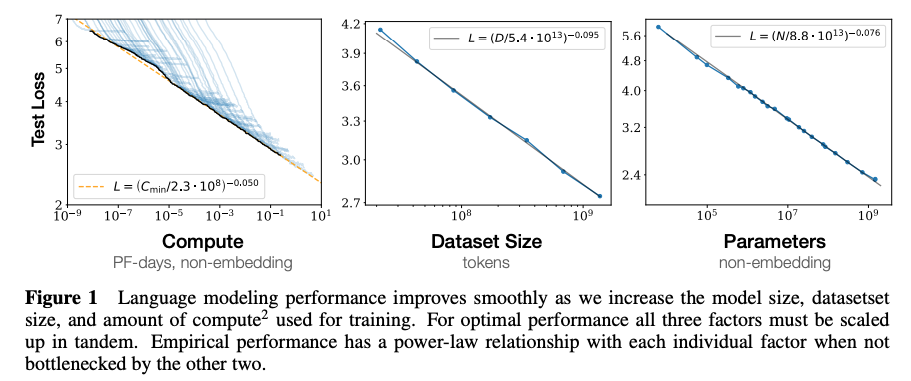

Now, can we actually predict the performance of larger models based on the performance of smaller models? An important paper by Kaplan et al. (2020) suggests that we can. They show that the performance of language models scales in predictable way with the number of parameters, dataset size and compute.Sample efficiency

As a side note, one interesting finding of the Scaling Laws paper is that bigger models are more sample efficient. This means that they need less data to reach the same performance as smaller models.

There might be technical studies related to this, but I recently heard two hypotheses, as the question was asked by Dwarkesh Patel to John Schulman (Co-founder of OpenAI) and Trenton Bricken (Anthropic). Their answers:

John Schulman:

(A bigger model is) learning all these different computations in parallel and you have more of them with a bigger model. So you have a higher chance that one of them is lucky, ends up guessing correctly a lot, and gets upweighted.Source

...

Just having a bigger model gives you more chances to get the right function. Of course, it's not just totally disjoint functions you're taking a linear combination of. It's more like a library where you might chain the functions together in some way. There's some composability. So I would say a bigger model has a bigger library of different computations, including lots of stuff that's dormant and only being used some of the time, but it has more space to look for circuits to do something useful.

Trenton Bricken:

One thing about the superposition hypothesis that interpretability has pushed is that your model is dramatically underparameterized and that's typically not the narrative that deep learning has pursued, right? But if you're trying to train a model on the entire internet and have it predict with incredible fidelity, you are in the underparameterized regime and you're having to compress a ton of things and take on a lot of noisy interference in doing so. When you have a bigger model, you can have cleaner representations to work with.Note: superposition can be defined as

If you are in a regime where your data is high-dimensional and sparse-by sparse I mean, any given data point doesn't appear very often-your model will learn a compression strategy that we call superposition so that it can pack more features of the world into it than it has parameters.Both quotes are from this podcast episode.

To characterize language model scaling we train a wide variety of models, varying a number of factors including:Within this range, the authors found that the performance of the language models scaled predictably with the number of parameters, dataset size and compute:

- Model size (ranging in size from 768 to 1.5 billion non-embedding parameters)

- Dataset size (ranging from 22 million to 23 billion tokens)

- Shape (including depth, width, attention heads, and feed-forward dimension)

- Context length (1024 for most runs, though we also experiment with shorter contexts)

In 2022, Google found different, even better scaling laws in their Chinchilla paper. This is mostly because they tuned the training hyperparameters for each model size.

However, we can see that the scale of the tested parameters in the original scaling laws paper is limited compared to today's largest models. Let's compare the tested hypothesis with Llama 3, one of the larger models publicly available today:| Model/Paper | Parameters | Tokens | Context length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaplan et al. (2020) | 1.5B | 23B | 1024 |

| Chinchilla | 16B | 1.4T | 2048 (?) |

| Llama 3 | 70B | 15T | 8192 |

Emergent behaviour in large language models

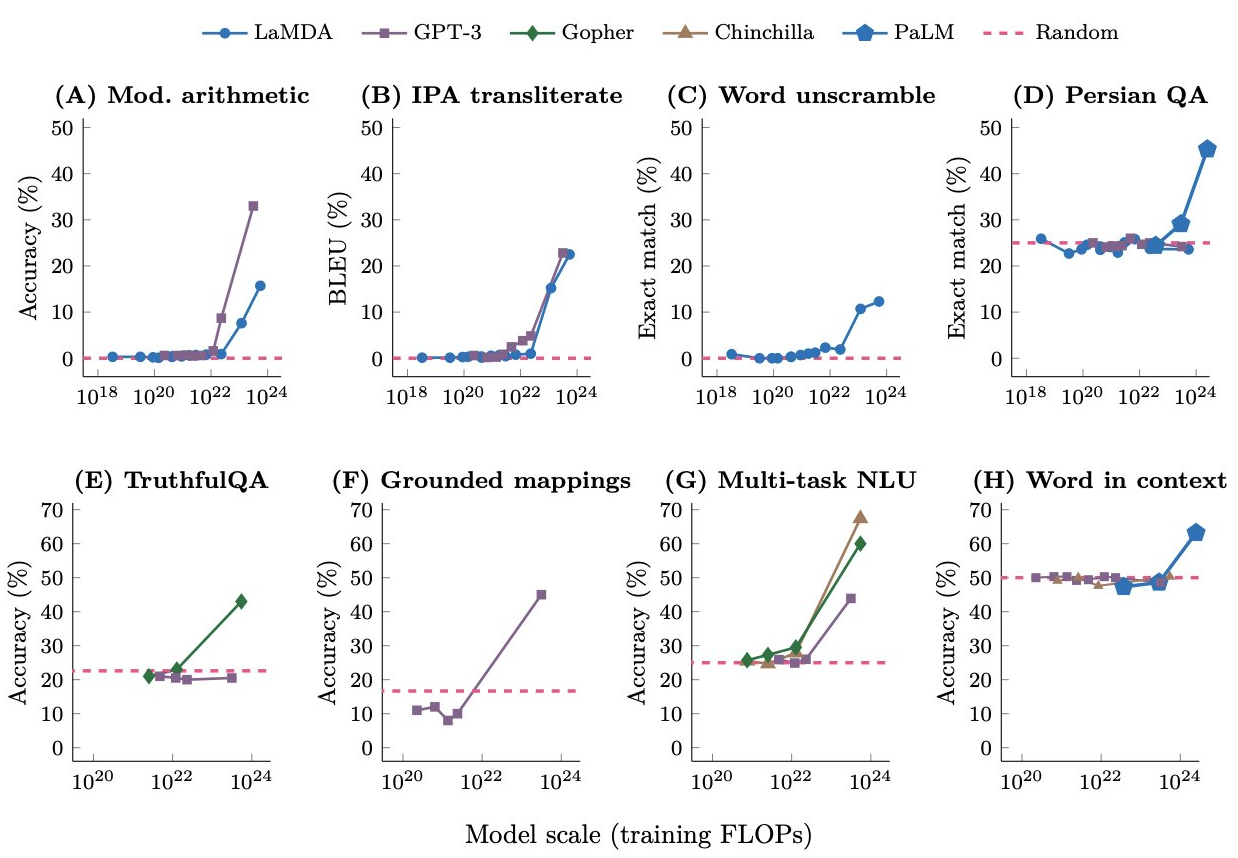

A few months after publishing the Chinchilla paper, Google published Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models, which suggested that at a larger scale, scaling laws do not completely hold anymore: We can see that at a certain scale, model performance suddenly increases, and no longer follows a predictable trendline. This was also stated in Google's PaLM paper:

We can see that at a certain scale, model performance suddenly increases, and no longer follows a predictable trendline. This was also stated in Google's PaLM paper:

... However, for certain tasks, we observe discontinuous improvements, where scaling from 62B to 540B results in a drastic jump in accuracy compared to scaling from 8B to 62B. Such behavior is observed on roughly 25% of the BIG-bench tasks in Section 6.2. This suggests that new capabilities of large LMs can emerge when the model achieves sufficient scale, and that these capabilities continue to emerge beyond previously studied scales.

Now, if the above is true, it would mean that it would be more difficult to do research related to large language models: if we suddenly see big jumps in performance, training smaller models will not give us much useful information about the performance of bigger models. Ergo, to test hypotheses related to large models, we actually need to train them. 💸🔥

Are Emergent Abilities of LLMs a Mirage?

Fortunately, a paper from 2023 questioned the above obversations. The authors won the NeurIPS best paper award for their findings. The paper is a great read - it states that most emergent behaviour is caused by using the wrong evaluation metrics. For example, it found that model performance is often measured by looking for an exact string match between the model output and a target sentence. Small models will typically not perform well when using this metric - but at some scaling point the model will predict the exact string match, and now it looks like the model suddenly got much better. But this performance improvement is in fact not a sudden change - the models were gradually getting better, approximating the exact string more and more. The core paragraph in the paper is the following:We call into question the claim that LLMs possess emergent abilities, by which we specifically mean sharp and unpredictable changes in model outputs as a function of model scale on specific tasks. Our doubt stems from the observation that emergent abilities seem to appear only under metrics that nonlinearly or discontinuously scale any model's per-token error rate. For instance, as we later show, > 92% of emergent abilities on BIG-Bench tasks [28] (hand-annotated by [32]) appear under either of these two metrics:A great reminder that choosing the right metric is important - and an important finding: emergent behaviour might not really exist, or at least does not exist to the extent that we thought it did.This raises the possibility of an alternative explanation for the origin of LLMs' emergent abilities: sharp and unpredictable changes might be induced by the researcher's choice of measurement, even though the model family's per-token error rate changes smoothly, continuously and predictably with increasing scale. Specifically, our alternative posits that emergent abilities are a mirage caused primarily by the researcher choosing a metric that nonlinearly or discontinuously deforms per-token error rates, and secondarily by possessing too few test data to accurately estimate the performance of smaller models, thereby causing smaller models to appear wholly unable to perform the task.

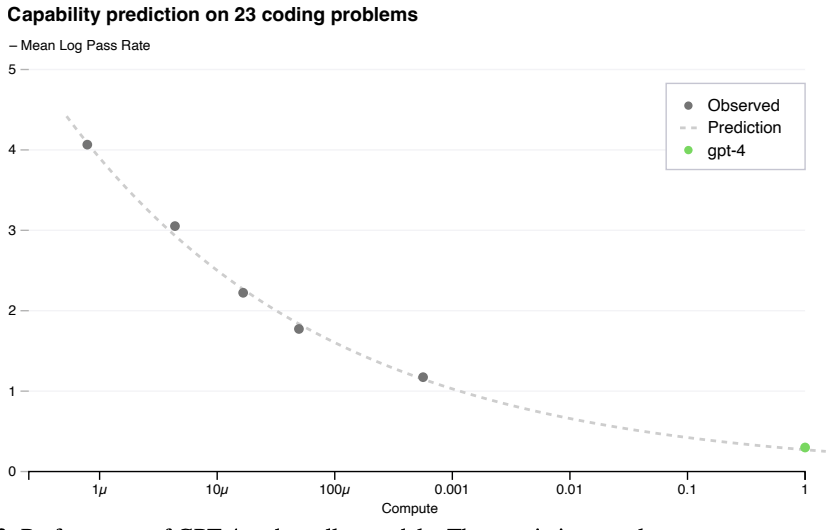

In the GPT-4 technical report, the scaling law can be predicted again as well with the right metric:

A large focus of the GPT-4 project was building a deep learning stack that scales predictably. The primary reason is that for very large training runs like GPT-4, it is not feasible to do extensive model-specific tuning. To address this, we developed infrastructure and optimization methods that have very predictable behavior across multiple scales. These improvements allowed us to reliably predict some aspects of the performance of GPT-4 from smaller models trained using 1,000× – 10,000× less compute.So, scaling laws might just work fine, or at least work better than suggested for some time.

Exceptions to scaling - inverse scaling prize

Unfortunately, the above does not mean that we can blindly trust scaling laws. There are exceptions to the rule, which makes LLM research more tricky - you cannot always assume that what works at a small scale, works at a larger scale. This is emphasized by Sholto Douglas (Google, Gemini) as well here:You never actually know if the trend will hold. For certain architectures the trend has held really well. And for certain changes, it's held really well. But that isn't always the case. And things which can help at smaller scales can actually hurt at larger scales. You have to make guesses based on what the trend lines look like and based on your intuitive feeling of what's actually something that's going to matter, particularly for those which help with the small scale.Now, let's look at a few of exceptions where scaling does not work. Note that here we will not discuss training techniques that work at a small scale but do not work at a bigger scale, but tasks where bigger models perform worse compared to smaller models.

The inverse scaling prize (2022) was a contest that tried to encourage participants to find important tasks where larger models do worse compared to smaller models. The findings are quite interesting, as the winners found 11 benchmarks where inverse scaling holds. The benchmarks fall into four categories:

- Strong Prior, for example Memory Trap: "This task asks an LM to write a phrase in a way that starts like a famous quote but ends differently. Larger LMs are more likely to continue with the famous quote, suggesting they struggle to avoid repeating memorized text".

- Unwanted imitation, for example Modus Tollens, repeating logical fallacies. The authors mention that this mistake might be made because humans tend to make it too — so as models get better at modeling human behaviour (or more precisely: modeling their training data), they will be more likely to make logical fallacies that humans tend to make.

- Distractor Task, for example: Pattern Match Suppression. This task tests whether LMs can be instructed to interrupt the repetition of a simple pattern.

- Spurious Few-Shot, adding correctly-labeled but misleading demonstrations of the task to the prompt. For example Hindsight Neglect, where LMs must assess if a bet is worthwhile based on its expected value (EV), given a prompt with examples where the outcomes of the bets match the EV, but the outcome in the final question does not.

There is some evidence (December 2023) that some inverse scaling tasks show U-shape scaling. That is, performance first goes down with scale, but then for really large models, performance improves again. However, this is not true for all tasks:

GPT-4 and GPT-4 RLHF performance varied between tasks: improved performance was observed on Modus Tollens, Into the Unknown, and Repetitive Algebra; mixed performance on Pattern Match Suppression; and poor performance on Memo Trap.Source: Inverse Scaling: When Bigger Isn't Better